Simplifying Fluid Delivery for Microfluidics

By Stefan Martin, Mechanical Engineering Team & Mike Fussell, Life Sciences Product Manager

Published on May 26, 2022

Microfluidic systems hold tremendous promise for high-throughput screening and the development of rapid, highly sensitive multi-omics medical diagnostics. High-throughput analysis of live cells and unparalleled reagent efficiency and process control can reduce reagent consumption and experiment time by orders of magnitude compared to traditional laboratory protocols. The development of organ-on-a-chip (OOAC) biomimetic systems which accurately model the microenvironments of organs are opening up new frontiers of drug discovery. This makes microfluidics an invaluable tool for both research and commercial applications.

Ensuring consistent and controllable fluid delivery is crucial to achieving reliable and repeatable performance from microfluidic devices. In this article, Zaber demonstrates an affordable fluid delivery system based on X-LSM linear stage-driven syringe pumps and compares it to pneumatic and electrowetting-based systems.

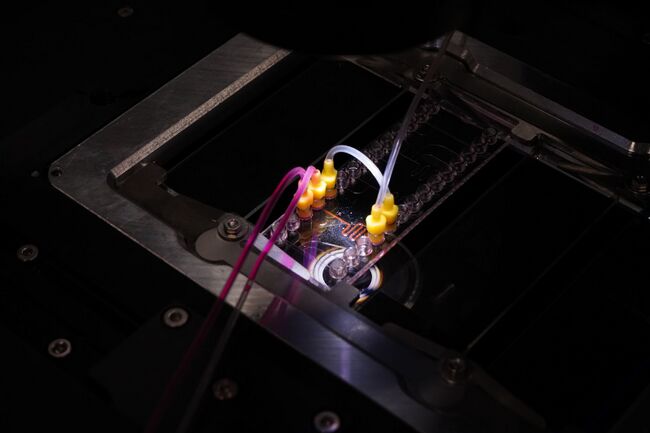

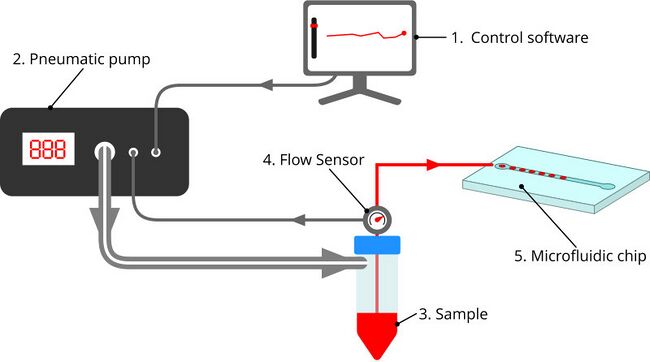

Figure 1. To function correctly, the droplet generator on the microfluidic chip must be supplied with fluid from an external reservoir.

Automated Fluid Delivery

While a wide range of microfluidic fluid pumping solutions are commercially available, many require external synchronization and do not provide a simple path to software integration. Developing a system using these components requires integrating multiple APIs and hardware triggers, greatly increasing the complexity of setting up and optimizing a system. Zaber’s daisy-chainable X-Series of motion control devices share the same control protocol and software API as the XY and goniometer stages used to drive the reference chip alignment system. This makes coordinated control of chip positioning and fluid delivery easy.

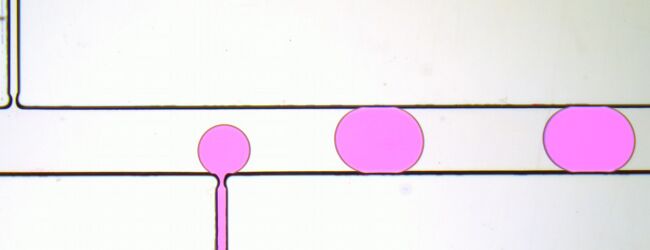

Figure 2. Droplet generator imaged with transmitted illumination using a Nucleus MVR microscope.

Automated fluid delivery systems should be easily programmable, highly consistent, and have a fast response time. Surveying the range of available fluid delivery options, three approaches stand out in their potential for simplifying fluid pumping automation for microfluidic systems.

Motion controlled syringe pumps

Stepper motor-driven syringe pumps are cost effective, easy to set up, and can be configured for flow rates of 100 pL/s to 10 mL/s. This approach provides excellent flexibility. Syringes can be switched to quickly change reagents, or change flow rates.

Zaber X-LSM linear stages with integrated controllers and submicron microstepping offer many of the features of state-of-the-art syringe pumps while also supporting daisy chaining using a single cable for power and communication. This greatly simplifies the combined control of imaging and fluid flow when used in conjunction with the Nucleus® MVR microscope. The Nucleus automated microscopy platform provides a complete set of interchangeable hardware modules and software tools for building your bespoke inverted or upright standalone microscope or optical subsystem.

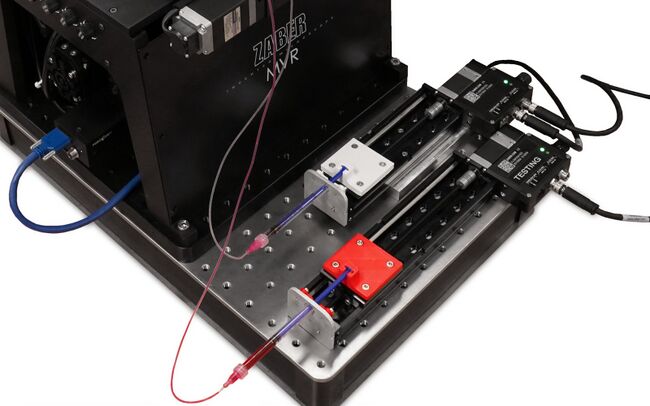

Figure 3. Example of a Zaber X-LSM100A converted into a 1 mL syringe pump. This stage offers sub-micron microstepping and can be commanded via a unified ASCII protocol common to all Zaber devices.

The components of this example system can be 3D printed and laser cut. The required files to print and cut your own can be downloaded here. This package includes:

- 1mL syringe plunger adapter (fits McMaster #7510A806)

- 1mL syringe holder

- 1ml syringe block

- X-LSM mounting plate

Sample code used by this example to convert linear motion into a flow rate. Prior to running this code, the syringe flow per distance should be measured by moving the stage a known distance and measuring the volume of fluid that is dispensed. Another, less accurate method is to simply measure the graduations on the syringe.

from zaber_motion.ascii import Connection

from zaber_motion import Units

SERIAL_PORT = "COM4"

We define a dict of syringe sizes with the measured flowrate and an optional point at which we have fully retracted the plunger. These will be different depending on the particular model of syringe used.

SYRINGES: dict = {

'1mL': {

'max_position': 30,

'flow_conversion': 0.01724, # uL/um

}

}

We create a flow control class for converting a requested flowrate to stage motion commands as well as starting and stopping the axis.

class FlowController:

def __init__(self, axis, syringe):

self.axis = axis

self.fc = syringe.flow_conversion

self.max = syringe.max

return

def start(self, flowrate):

# inputs: commanded flowrate [uL/s]

print("Commanding flowrate to %.2f" % flowrate)

self.axis.move_vel(flowrate / self.fc, Units.VELOCITY_MICROMETRES_PER_SECOND)

return 1

def stop(self):

self.axis.stop()

return 1

def stop_at_limit(self):

# Can also be implemented using firmware triggers

if self.axis.get_position(Units.LENGTH_MILLIMETRES) > self.max:

self.axis.stop()

return 1

else:

return 0

We instantiate 2 instances of the class above, dropletPhase and contPhase, one for each pump we wish to control.

with Connection.open_serial_port(SERIAL_PORT) as connection:

device_list = connection.detect_devices()

LSM1 = device_list[1].get_axis(1)

LSM2 = device_list[1].get_axis(2)

contPhase = FlowController(LSM2, SYRINGES['1mL'])

dropletPhase = FlowController(LSM1, SYRINGES['1mL'])

Running this system is then as simple as calling the start() method with the desired flowrate in µL/s. We can optionally watch the position of the stages to make sure it doesn’t exceed the limits we set up. This can also be accomplished with Zaber’s firmware triggers.

contPhase.start(10.5)

running = dropletPhase.start(2.1)

while running:

running = not contPhase.stop_at_limit() and not dropletPhase.stop_at_limit()

One limitation of stepper-motor syringe pumps is that at very low flow rates the stepping behaviour may be visible in the flowrate. Additionally, stiction inherent in leadscrew-driven stages means the stage will not move on every microstep. This may lead to small errors in the fluid flow rate delivered by the system. This effect is explained in detail in Zaber’s actuator-precision-characterization whitepaper. With some preliminary tuning, the X-LSM example above was able to achieve a RMS flow rate error below 3nL/s.

The final metric for flow noise is droplet size consistency. Accurate measurement of droplet sizes and their flow rates is possible by imaging the droplets. The Nucleus MVR inverted microscope provides a simple and cost effective platform for moving shot imaging. More detailed information on how the Nucleus MVR can help eliminate the need for expensive high-speed imaging can be found in the article on Simplifying microfluidic Imaging.

Figure 4. Sample of droplets formed with 0.4 μl/s continuous phase (HFE 7500, 2% flowSurf), 35nL/s droplet media flow rate controlled with Zaber LSM stages.

Pressure-driven (Pneumatic) Pumps

For applications which need higher consistency, pneumatic pumps offer the smoothest flow rates. Their responsiveness is typically faster and the lack of step changes in pressure ensure that the flow is virtually free of periodic fluctuations. This results in low droplet size variance. While pneumatic pumps perform well, they are costly and complex. These pumps are not based on a volumetric process, which necessitates feedback control to maintain their desired flow rates. This makes them more expensive and time consuming to set up. Multiport pneumatic systems can easily cost more than $10,000.

Figure 5. Pneumatic pump-driven system takes a target flow rate from software (1) which controls a pneumatic pump (2) that dispenses the sample (3). A flow rate sensor (4) measures the flow rate and provides feedback control to the pump ensuring an accurate and consistent flow rate to the chip (5).

On-chip Electrowetting

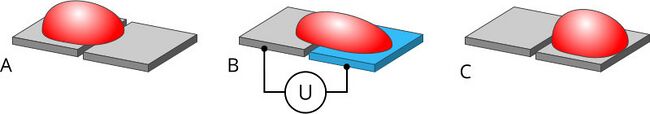

On-chip electrowetting or Digital Microfluidics (DMF) is emerging as an attractive alternative to conventional chip-based microfluidics. DMF devices operate like an FPGA for microfluidics which allow arbitrary operations on droplets configured and controlled directly from software. Droplets are pulled around the device using an array of high voltage electrodes which manipulate the droplet surface tension using the electrowetting effect.

Figure 6. A DMF device moves droplets moved from one (A) cell to the next by sequentially energizing electrodes (B).

To achieve full automation of a DMF system requires precise control over reagent loading and droplet generation, and optimized pathing. Droplet generation requires a DMF chip to be “loaded” with reagents to supply droplets to the system. Dispensing precise fluid volumes in small areas is a task best accomplished by an automated pipetting system. Zaber motion control devices can provide an effective and versatile solution for positioning and dispensing liquids by adapting the syringe pump presented earlier in this article (Fig. 6).

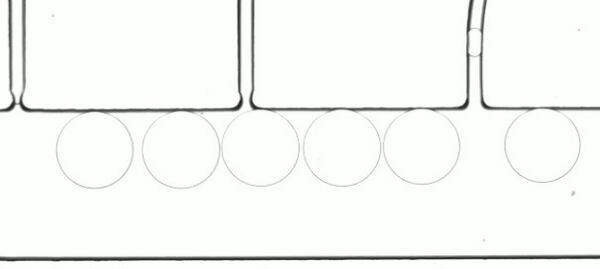

Figure 7. Sequence of droplet generation from a reservoir loaded with reagent.

Droplet pathing is a non-trivial exercise. Current DMF chips cannot operate at the kHz droplet rate of other microfluidic technologies, so optimizing the time for processes is crucial. For complex reactions or high throughput it is always desirable to minimize the path travelled by droplets. To avoid contamination, electrode pads should not be reused for multiple reagents.

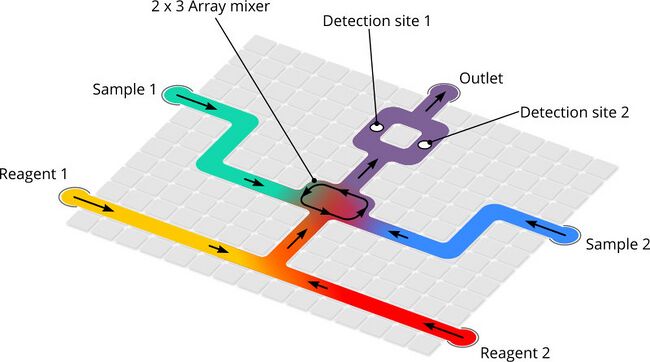

Figure 8. Example pathing for DMF microfluidic device. Routing prevents contamination of reagents and samples by ensuring paths do not cross outside of intentional mixing operations.

The main drawbacks of DMF are evaporation and environmental instability of the droplets deposited on the surface. Currently available hydrophobic dialectic coatings such as ETFE film coated with silicone oil are extremely susceptible to contamination and may only last 2-3 days13 before they must be reapplied. A cleanroom or a clean box with a HEPA filter surrounding the system is highly recommended to prolong the coating’s life. Imaging-based monitoring and feedback is more complex to implement with DMF than with other microfluidic techniques as the substrate’s opacity prevents the use of transmitted light imaging.

Summary

Automating fluid delivery is ultimately a highly process-dependent decision. However, for users who want to get up and running with microfluidics in a manner of minutes, syringe pumps driven by Zaber precision linear stages can be an attractive option for prototyping. The system shown above is a highly configurable microfluidics platform which eliminates the need for costly single-purpose equipment and has the potential to remove many time consuming manual operations through automated chip registration and high-speed imaging. This opens the door to scaling high-throughput screening operations and developing innovative new diagnostics.