Streamed and Interpolated Multi-Axis Motion

By Mike McDonald, Applications Engineering Team

Published on Jun. 09, 2014

Introduction

Zaber's X-MCC series of controllers offer the ability to use streamed and interpolated multi-axis motion. This article discusses the capabilities of this feature and how it can be used. It is not meant as a detailed resource for the commands, and the ASCII command reference should be referred to for that purpose.

Pre-emptive Commands vs. Streamed Commands

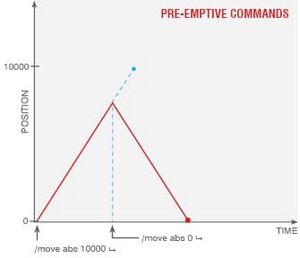

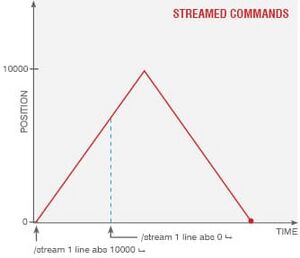

All the commands in Zaber's protocols excluding the stream set of commands are pre-emptive, which means that the commands will be run as soon as a controller receives them.

For instance, when a movement command is sent, the stage will immediately accelerate from a stop up to the targeted speed and move towards the requested position. If a new command is then sent that isn't compatible with the current command being executed, the newer command will take precedence and pre-empt the existing command.

If the stage mentioned above receives another movement command while halfway through the first command, it will immediately change course to target the new position, pre-empting the first movement. Another example is if the speed setting is changed midway through a movement, the stage will immediately accelerate or decelerate to reach the new speed target.

In contrast, streamed commands are executed in the order that they are received, with each command completing before the next command begins. The timing of when they are received doesn't matter - only the order. In the example above, where two movement commands are sent in series, streamed movement commands ensure that both points are reached.

Pre-emptive commands force the user to coordinate the timing of when commands should be sent. If it's important for a movement to complete before continuing, then the user must continually poll the device to see when the state has changed from BUSY to IDLE so that they know when they can send the next command. In contrast, streamed commands allow much more certainty on the timing, as the responsibility is offloaded from the user to the controller.

Diagrams illustrating pre-emptive and streamed commands are shown below:

|

|

Command Queue

To manage how a stream of commands is executed, the controller creates a queue of received streamed commands when the stream is set-up. The queue gets smaller as commands are executed, and fills up as more commands are sent. If the queue empties completely, the device will treat this as an end of the commands and decelerate to a stop. A warning flag is set to indicate this, as it may be a result of commands not being sent fast enough.

Conversely, if the queue fills up completely, the controller will respond with AGAIN to any additional streamed commands. The user should continue to send the last command to the controller until some of the previous ones have completed and the queue is no longer full.

While streamed commands are useful when movements are predictable, pre-empting is sometimes desired when movements needs to be more dynamic. To accommodate this, pre-emptive commands will still interrupt streamed commands. For example, a stop command will still stop streaming motion as soon as the controller receives it. This way, you can combine both types of movements based on the requirements of your system. Any movements set up in triggers may also interrupt the streamed commands.

Independent vs. Interpolated Motion Commands

One advantage of using streamed commands instead of pre-emptive ones is that it allows movements to be much more predictable. This lends itself to coordinating the motion of multiple axes together, which is one of the main reasons that streamed commands have been introduced.

Non-streamed commands are either addressed to a single axis or the same command is sent to every axis, and, either way, each axis will interpret and execute the command separately. Speeds and accelerations are also axis independent. The result is that while each axis has a known path, it's difficult to predict or control the combined path of more than one axis.

Streamed movement commands may address multiple axes, and the positions, speeds, and accelerations of the axes will be interpolated to make a determinate multi-axis path. The different paths are known as geometric motion primitives.

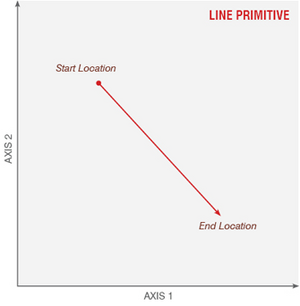

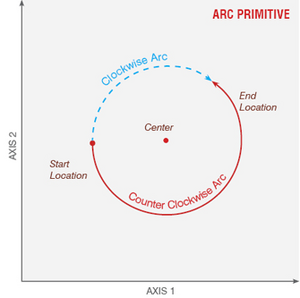

Geometric Motion Primitives

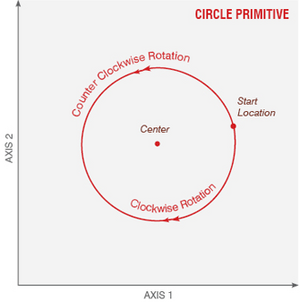

A geometric motion primitive is a building block shape. The primitives that are currently available are lines, arcs, and circles. These primitives can be combined in series to make up more arbitrary shapes or series of movements.

The line primitive will move one or more axes to an end point, or by a desired amount. The arc primitive will move a circular arc to a targeted end point, with the direction of movement and the center of the arc defined by the user. The circle primitive makes a complete revolution which only requires a direction and a center, as the end point will be the same as the start point. The line primitive can be applied in any number of axes, while the circle and arc can work in any two dimensions of the stream. Using these three building blocks, you can closely approximate other shapes and curves.

Diagrams illustrating each motion primitive are provided below:

|

|

|

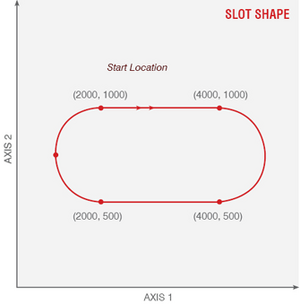

Converting from NC Code

Line, arc, and circle primitives are standard in numerical motion control (NC). Each shape also has direct equivalents in G-code, the most widely used NC code. A sample of G-code that moves in a slot shape is provided:

...

G0 X2000 Y1000

G1 X4000 Y1000

G2 X4000 Y500 I4000 J750

G1 X2000 Y500

G2 X2000 Y1000 I2000 J750

...

All values are absolute and in microstep units.

The G0 and G1 commands both represent line movements, while the G2 and G3 commands create arcs in clockwise or counterclockwise direction, respectively. G-code does have some variation in whether absolute or relative points are used, and whether arcs are defined by a radius or a center point, so care should be taken with the coordinates if they're used with Zaber controllers. A sample of stream commands for slot shape are provided below:

/01 stream 1 setup live 1 2 ↵

/01 stream 1 line abs 2000 1000 ↵

/01 stream 1 line abs 4000 1000 ↵

/01 stream 1 arc abs cw 4000 750 4000 500 ↵

/01 stream 1 line abs 2000 500 ↵

/01 stream 1 arc abs cw 2000 750 2000 1000 ↵

...

Note that the end point and center point of the arcs are reversed from the g-code.

|

Additional Streamed Commands

In addition to the motion primitives, there are other stream commands that can be added to the queue and executed in order.

Waiting and I/O Controls

Wait commands allow you to add more timing control into a stream. Wherever a wait command is inserted in the stream, the movement will slow to a stop, wait for a condition to be met, and then continue on with the next command. The condition can either be a certain amount of time elapsing, or a certain value on one of the X-MCC's digital or analog input pins. The input isn't checked until the moment when the axes come to a stop.

In addition to waiting on inputs, you can also toggle the X-MCC's digital outputs in the stream. If a command to toggle the output is between two motion commands, the output will toggle without any interruption in the motion. Some situations where this might be useful include triggering a sensor to take a reading, turning a laser on or off, or triggering a camera to capture a photo, all with accurate positioning and without stopping motion.

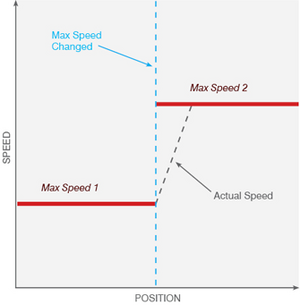

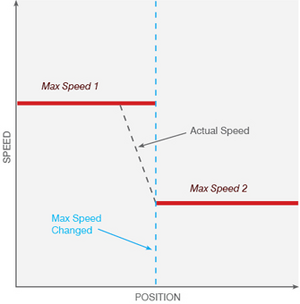

Setting Physical Constraints

The speed and acceleration settings for the stream can also be changed mid-stream. These settings are independent of the settings of individual axes, and they relate to the combined movement of all axes in the stream.

If a command to change the setting is in the stream of commands, it will take effect so that all of the constraints are obeyed before and after the setting change.

As an example, if the speed is initially 5000 but is set to 3000 between two streamed movements, the stage will start to decelerate near the end of the first movement so that it reaches 3000 by the time the second movement starts. The constraint in this case is that the speed of 3000 is a maximum, and the updated setting should not be exceeded during any part of the second movement.

Conversely, if the new setting were 8000, the acceleration would occur during the second movement in order to obey the first movement's maximum speed constraint over its full length.

Diagrams illustrating speed settings are provided below:

|

|

In addition to the maximum speed, there are two acceleration settings that are obeyed: tangential acceleration for changing the speed, and centripetal acceleration for changing direction (for arcs and circles).

As mentioned in the introduction, you can read more about the complete command set in our ASCII command reference. Information about potential uses is available in our application note about 2D Interpolation.

Feel free to contact one of our Applications Engineering Team at contact@zaber.com if you have any questions about this article, if you have a potential application in mind, or need any other additional information.